The International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) is a storied labor union, deeply entwined with the history of labor movements on the West Coast of the United States. Its origins trace back to 1937, a time when longshore workers and warehouse employees faced grueling conditions, extremely dangerous job sites, meager wages, and exploitative labor practices that treated longshoremen as expendable and disposable.

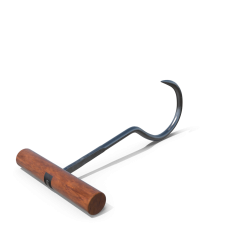

In those days, longshoremen relied on a simple yet crucial tool known as the "T Hook" or "hay hook." This tool, essentially a long-handled, curved hook with a T-shaped handle, was vital in manually stowing cargo in the holds of ships. Longshoremen used these hooks to secure and position heavy and unwieldy loads within the vessels such as cow hides or ice blocks, often in challenging conditions.

The "T Hook" became an enduring symbol of the resilience and determination of longshore workers during this era. It represented not only the physical demands of their work but also the inherent solidarity of dockworkers.

Established as a response to these harsh conditions, the ILWU swiftly gained prominence under the leadership of notable figures such as Harry Bridges. One of the most pivotal moments in its history occurred during the 1934 West Coast waterfront strike, a defining chapter that saw the loss of two men's lives during altercations with San Fransisco riot police on July 5, 1934. This day is known as "Bloody Thursday"; a day commemorated every fifth of July by ILWU members along the West Coast.

Throughout its evolution, the ILWU has upheld the motto "An Injury To One Is An Injury To All." This rallying cry underscores the spirit of solidarity among its members.

Over the decades, the ILWU expanded its influence, encompassing various sectors, including agriculture, fishing, and warehousing. The union also took up the mantle of advocating for civil rights, with Harry Bridges and the ILWU actively promoting equality for all workers, regardless of their racial or ethnic backgrounds.

Today, the ILWU remains a formidable presence in the labor movement, representing workers along the West Coast of the United States, Hawaii, Alaska, and Canada. An unwavering commitment to solidarity and the pursuit of fair labor practices marks its history. The "hay hook," once a symbol of both the toil and skill of longshoremen, has now transformed into an iconic emblem of the enduring longshore spirit and has itself become better known as the "Longshore Hook".

As the ILWU journeyed through the decades, it carried with it the legacy of those who came before, who labored tirelessly with their longshore hooks in hand. The challenges they faced, the sacrifices they made, and the solidarity they displayed continue to shape the identity of the ILWU and its members today.

In an ever-evolving world, the ILWU stands as a testament to the power of collective action, the importance of fair labor practices, and the enduring symbol of the longshoremen, reminding us of the tenacity and strength of those who have shaped this union. The ILWU's commitment to equality and the welfare of its members remains as resolute as ever.

Harry Bridges: A Labor Icon and the Founding of the ILWU

Harry Bridges, an influential figure in the American labor movement, is celebrated for his steadfast dedication to the rights and well-being of dockworkers and warehouse laborers on the West Coast. His life and career were characterized by persistent labor advocacy and played a pivotal role in the formation and growth of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). Bridges' story is not only one of relentless labor activism but also one of enduring multiple prosecutions and false accusations by the U.S. government, falsely labeling him as a Communist.

Early Life and Arrival in the United States:

Born on July 28, 1901, in Kensington, Melbourne, Australia, Harry Bridges embarked on a journey that would ultimately reshape the labor landscape in the United States. In his youth, he worked in various jobs, including as a seaman, which led him to cross the Pacific and settle in San Francisco, California, in 1920.

Formation of ILA Local 38-79:

By the 1930s, the working conditions for waterfront laborers along the West Coast were deplorable, marked by meager wages, job insecurity, and harsh treatment. Bridges, inspired by the burgeoning labor movements across the country, became deeply involved in the struggle for workers' rights. He played a central role in organizing the longshoremen and warehouse workers in San Francisco and beyond.

In 1933, Bridges and other dedicated activists established the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA) Local 38-79. This local union sought to represent the diverse workforce of dockworkers, many of whom were immigrants, responsible for loading and unloading cargo on the bustling waterfront. Under Bridges' leadership, Local 38-79 rapidly expanded its membership and influence.

1934 Maritime Strike and the Birth of the ILWU:

The watershed moment in Harry Bridges' career arrived with the 1934 West Coast maritime strike. This historic strike, originating in San Francisco and cascading along the coast, emerged as a massive and at times violent confrontation between waterfront laborers and the powerful shipping companies. Bridges emerged as a prominent leader of the strike, galvanizing workers and coordinating their efforts.

During the strike, Bridges recognized the need for a more unified and comprehensive approach to organizing and representing maritime workers. In response, he played a pivotal role in founding the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union (ILWU) in 1937. The ILWU aimed to bring together longshoremen, warehouse workers, and other related labor groups under one banner to enhance their working conditions, secure better wages, and fortify job security.

False Accusations of Communism:

Harry Bridges' dedicated labor activism and his influential role within the ILWU made him a target for the U.S. government during the Red Scare era, characterized by intense scrutiny of alleged Communist ties. Authorities repeatedly accused Bridges of harboring Communist sympathies and sought to have him deported. These allegations were part of a broader anti-Communist sentiment in the United States, leading to the infamous McCarthy era.

Between 1939 and 1955, Bridges endured four separate deportation trials. However, despite the government's relentless efforts to prove his alleged Communist affiliations, Bridges was never successfully deported. Throughout these trials, he consistently maintained his innocence, emphasizing that his primary concern was the well-being of workers and their rights. His steadfast assertion that he was not a Communist was corroborated by various investigations and testimonies.

Enduring Contributions and Legacy:

Harry Bridges' leadership within the ILWU continued for decades, and his legacy is marked by significant achievements for union members, including improved wages, enhanced working conditions, and fortified job security. Bridges remained committed to workers' rights until his retirement in 1977.

Beyond his labor leadership, Harry Bridges became an iconic figure in the American labor movement, celebrated for his unwavering determination and dedication to the well-being of working people. His profound contributions to the ILWU and the broader labor movement continue to be remembered and honored.

Harry Bridges passed away on March 30, 1990, leaving behind a remarkable legacy of labor activism that continues to inspire and shape the labor movement in the United States.